Findings: Achieving Gender Equity in High Performance Athletics Coaching in the U.K.

Representatives from each of the four home countries and UK Athletics were interviewed to explore their perspective and approaches towards the issue of gender equity within their high-performance coaching workforces. The following section outlines the key themes to arise from these interviews. In summary, the data suggests that the governing bodies understand broadly, the need for gender diversity amongst their coaches and some of the benefits that will come from greater representation amongst men and women. Their understanding of these benefits has shaped their interventions and approaches to this issue. From this, it is clear that the governing bodies express a degree of readiness for change and willingness to tackle the long-standing issue of representation of women at high- performance levels of coaching. Nevertheless, because of the existing culture of many clubs and governing bodies, many of these strategies have limited impact. The approach taken is within a performance-driven, metrics-based culture. The approach has then been one of either a ‘fix or equip the women’ and / or of creating ‘equal opportunities’ rather than a transformative, progressive vision. The four sections that follow, provides depth to this argument supplemented by quotes by the participants.

Organisations recognise the need for greater diversity amongst their high-performance coaches for their athletes

The interviewees agreed that gender equity was a need amongst their coaches. Equity in this way was conceived as an issue of diversity; it was important to have a greater number of women represented in high- performance coaching. The benefits of this were largely seen from a potential impact and benefit on athletes, in particular, to meet a greater diversity of athletes and to improve participation if there is a greater degree of choice of coaches and coaching expertise. The issue of giving athletes choice was important to the following NGB representative:

If you see that there’s only one gender of coaches that are kind of, at each stage across the pathway, right the way from grass roots through to high performance, it may almost seem like a road block to some people, or it may be a barrier. Some people maybe respond better to being coached by a male figure whereas some people, including males, they may respond better to being coached by a female. It ultimately comes down to the athlete or to the group that you’re working with and the type of learners and the type of athletes that you have, how they respond. (NGB representative one)

Through giving potential and existing athletes choice, the NGBs recognised that they are more likely to meet the diversity of needs that athletes will have, and this will likely lead to improved retention and progression of participants. The NGBs expressed an athlete-centred approach in their rationale for greater diversity amongst coaches:

If we could have as diverse a coaching workforce from clubs right up to performance, up to talent, then that means that as an organisation and as a sport, we are more likely to meet the needs of most of the athletes which is what we are there for at the end of the day…I think if we have a broader workforce then we are more likely to meet the individual needs of the athletes and more likely that they will stay in the sport and progress through the sport. (NGB representative two)

More specifically, for one NGB representative, greater diversity amongst coaches was also a way of providing role modelling for female athletes (in the case for having a greater number of women coaches).

It’s very important, I think from a modelling perspective within our sport in order for females to be able to see themselves within our sport, whether it’s as an athlete or a coach, it’s so important that we have that, or we reduce that gender disparity (NGB representative three).

The value of greater diversity of coaches was a way of providing relatability for athletes who may not identify with the norm or dominant social group (White, non-disabled, male, and / or middle-class):

So, for me, parts of the country for example, the actual balance of athletes from different ethnicities is more white than black or ethnic minority backgrounds. So, for me when you’ve got an athlete with that ethnicity coming into a [national] setup for example, it’s even more important that there’s a role model there for them. (NGB representative four)

In summary, all the NGBs understood the value of a greater representation amongst their coaching workforce. Principally, this was to serve athlete choice, provide greater relatability between athletes and coaches, and act as a form of role modelling to athletes that women are credible and able leaders. The participants agreed that this will likely improve athlete performance if they experience a more connected, conducive, personalised coaching relationship.

Organisations recognise that there is work to be done to improve gender equity amongst their high- performance coaches and are ready to change

While the NGBs recognised the importance of greater diversity amongst their coaches, they also recognised that there is a long-standing gender ‘problem’ within athletics coaching. The participants interviewed were not gender-blind; there was a recognition of the problem of a lack of women particularly in high-performance coaching:

I don’t think we are anywhere near where we should be. And that is evidenced by the numbers, certainly as you go up the coaching qualification tree. (NGB representative five)

I think what we found is that we do have very good coaches at that level, you know we’ve got people coaching good developmental levels certainly…But actually if you go the step or two up, to athletes that are representing at major or even medalling at major then it’s a male dominated environment again. (NGB representative four)

Because of this, there was a degree of readiness for change amongst the NGBs. Some interviewed expressed a will to address the lack of gender equity amongst coaches:

Targeting female coaches into the pathway and into the development programme is something that we could do better. (NGB representative four)

To say this is where we are: it ain’t acceptable and let’s start making some change…We are massively under-represented [of women]. At high performance level… nothing more really to say, we need to address it. (NGB representative five)

It is not clear from the interviews as to what is driving this readiness to change – whether it has been a forced change, because of a change in leadership, or a deeper awareness of the issues that exist through listening to their coaches and athletes. For one participant, he admitted he did not always recognise the problem but that through a challenge by a female coach, he realised that he had been gender-blind in his approach. This demonstrates at least a willingness or openness to change:

A message from me to my team is that we have to make sure that we are better at including more women on teams in senior team coaching positions and in delivering webinars, workshops, conference etc. And I will hold my hand up and say, [it is] because we got challenged…it was a female coach who came to us and said ‘I’ve analysed your speaker numbers across the webinars you have delivered over the first two or three months and it is predominantly white male blokes…What are you doing about women delivering these? And I looked at the data, and they were absolutely right, and I held my hand up and said yeah good point. (NGB representative five)

The participants were honest in their appraisals of their organisation’s approach to issues of gender equity and agreed that what they have been doing has not worked or tackled the issue of women’s long-standing absence and exclusion from high-performance coaching. This is perhaps because gender equity is still conceived as a numerical issue – one of representation. Therefore, actions have largely been targeted towards increasing the numbers of women coaches and improving access to existing opportunities. This will be discussed in greater detail in section 3.3.

While there is a recognition of both the value of greater diversity and the need and will to address it, there was also the view that the approaches to improving diversity and inclusion amongst coaching have not been sufficiently rigorous, proactive, consistent, sustained, or deep-rooted to have the intended impact. One home country stood out from the others in terms of their greater recognition of the problems and willingness to tackle them. But across the four countries, as one participant remarked, the NGBs have not been committed to change and this is evident through a lack of consistency:

This is perhaps as an organisation [we] fall down a little bit in that there is from time to time the odd programme, you know we’ve had female coaching conferences in the past and we’ve had topics that we’ve picked up that may have been more of interest to female coaches. But with the exception of a target…we don’t do as much as we should to encourage women into the coaching pathway… When we get to the other end of things to the sort of two top level qualifications, for level 3 or the level 4, the numbers are completely reversed, and the majority is men. So probably, I’m gonna put my hand on my heart and say, [we don’t do] not as much as we should or could. (NGB representative four)

We haven’t had any programmes that I’m aware of since I came into post…that have targeted women specifically, sadly… There’s not enough targeted stuff being done (NGB representative four)

Grounded in the existing culture (as described by the coaches in the earlier section) of lack of transparency in decision making and a lack of a clear process for recruitment, one participant admitted that they take the ‘easy’ option of asking people already known to the organisation to lead coaching and events etc:

We reach out to the easy people that we know that will just go and deliver stuff. So, it’s lazy. (NGB representation five)

In the following section, we outline the types of strategies and initiatives that have been taken by NGBs to address what they have conceived to be the problem: a lack of representation of women in high-performance coaching.

Popular approaches and strategies to tackling gender inequity in athletics coaching

From an analysis of the data, it is clear that gender equity is conceived as a representational and an access issue – the participants talked about the need to address the acute imbalance of numbers of male and female coaches at high-performance levels, and the need to provide developmental opportunities for women coaches at this level. Some work has been carried out across the four home countries then to address this. One popular approach has been to take a targeted and quota stance (on occasions at least) to ensure women are represented at events and at points of the coaching pathway:

Our coach development lead…[they] would always be keen to have [women coaches] delivering. Simply because [they] know that that’s an area that is very underrepresented at a high-performance level,

particularly [in our country]. So, where possible she always would try and recruit a top female coach where possible to deliver [a course]. (NGB representative one)

Within our development pathway, we have recently made a significant push to make sure that three are females represented in those places. It is something that we are going to work towards over the next couple of years, with female coaches who show an appetite to develop in that space… At club level we do audits within their coaching infrastructures and they highlight if there is a clear gender disparity. (NGB representative three)

Another approach adopted by the home countries has been one of developing the women themselves based on the assertion that women coaches require greater capability and confidence in high-performance contexts:

We are going to work with [women coaches] to either support that development and provide further opportunity for them to kind of be, I guess, feel confident and competent in that arena. (NGB representative three)

We’ve also put on a number of coach development opportunities, that kinda focus on female athletes, but also female coaches as well, so we’ve put on a number of coach development seminars and workshops that look at female athlete health in the attempt to upskill the female coaches that we have. (NGB representative one)

For one participant, there appeared to be a ‘special casing’ of women and a conception of them as ‘different’, and therefore, coaches needed to understand how to work with such differences. However, it is clear from the following excerpt that difference was a negative connotation:

But also, to upscale the male coaches that we have, who are maybe working with female athletes as well. You know, because the type of topics and subject that they would maybe discuss as part of the female athlete health workshops would quite uncomfortable for some males and maybe even for some females to have some conversations about, so it’s trying to break down those barriers and empower all our coaches…to be able to recognise signs and symptoms of different deficiencies that maybe some athletes may have. But to also empower them to know what to do about it. (NGB representative one)

This approach of ‘special casing’ women also extended to coaching and led to the creation of women-only or women-focused programmes:

We do as I say, have a level 2 focus within female coaches going to the level 2 qualifications, we do have a little bit in there. (NGB representative four)

We’ve had topics that we’ve picked up that may have been more of interest to female coaches. (NGB representative four)

We have done some closed courses for female coaches, females that want to be coaches only. So, they have done some specific courses on particular groups (NGB representative two)

It is clear from the coaches’ stories in section 2.0 that such interventions are not positively received, desired, or have the intended impact. It is a fair assertion that the NGBs do not always know what is needed to tackle the gender inequity that exists within high-performance athletics coaching. This is particularly because they do not have the tools or levers for change, such as a central diversity and inclusion strategy or policy:

How do we actively do it (improve gender equity)? It’s not written down, which is probably a fault… We are collecting data though on who is delivering and who is on our coaching teams and we are doing this across all [the national] coaching teams…It was an internal target that we put down and this is how bad it is, I have forgotten what that target was…erm, around increasing the number of women we have on teams and diversity of our team staff…Is it as tight as it should be? No. Is it as coordinated or structured as it should be? No. Do we do it? Yes. (NGB representative five)

Efforts are also hindered by a lack of professionalisation and pathway for coaches in general. This was a significant issue also recounted by the coaches in section 2.0. This evidences the link between the wider structural issues within athletics coaching and its impact on addressing inclusion issues:

I have to be honest with you, we probably don’t have anything that’s really set down as a step to ensure that the coaches we’re working with are developing in the right way and have the right qualities and experience that perhaps they will need to continue with their athletes or their own development.(NGB representative four)

This section has highlighted some of the common approaches adopted by the NGB towards addressing what they understand to be the ‘problem’: a lack of representation of women coaches and the need to provide developmental and access opportunities for women. From the coaches’ accounts, it is clear that these attempts have not worked and the NGBs are honest in their appraisal that they are unsure of the approach to take. Any strategies have largely been inconsistent and there is no evidence of a collaborative, consistent, or strategic approach to diversity and inclusion. The following section outlines why this may be the case.

Performance-narrative and metrics-based culture driving organisations and undermining diversity and inclusion approaches

As described in the coaches’ accounts in section 2.0, there are significant issues within the culture of high- performance athletics coaching that are hindering or stopping entirely, women’s professional development and detracting from their sense of belonging within their clubs and organisations. Through the current culture, NGBs are limiting their understanding and vision of gender equity. First, because the current culture is metrics-based and underpinned by a performance narrative. The NGBs generally measure success in statistics and numbers, such as medals because this is the basis of funding:

I mean some of our stuff is driven by, again, [the NGB] and…targeted to medals in the way that other funding is done. So, we have to put a little bit of a nod towards that rightly or wrongly because that’s how we’re funded (NGB representative four)

Interviewer: How does your organisation measure success?

Respondent: It would be how many athletes maybe medal at a major championship (NGB representative one)

I mean there is a lot of things that we measure success on, so integrity of the brand is very important, well I know it’s very important to [the NGB]. Part of that brand is medals. (NGB representative two)

Success is also metrics-based in terms of coaches attending courses, athletes registered and attending Championships, and the number of affiliated clubs:

We try and track and measure success through the number of coaches both male and both female that are attending each of our coach education courses to see if there’s a trend if numbers are continuously increasing, to see if were meeting demand or to see if we need to be putting more courses on. Similar for our affiliated athletes, we look at the number of males and females that are registering annually. (NGB representative one)

[It shouldn’t be about] stats, it’s not we’ve got x amount to the Europeans, the Worlds, the Olympics… [But] we do have to recognise that those are stats from which we are funded. So, those are a measuring tool of success if you like (NGB representative four)

This then drives a performance-narrative across the organisation whereby athlete success is used as a measure of coaching effectiveness:

We do measure success by other means and again it’s just success stories mostly. You know, people who have, from a coaching perspective for example, managed to develop an athlete further than we anticipated the athlete can go. (NGB representative four)

As a sport, we appear to have measured it by the fact that you have got that athlete to a major Championship and they have performed well. Which is obviously only one tiny measure, of whether you are a good coach or not. (NGB representative five)

A lot of people do focus quite heavily on the outcomes and what the athlete achieves (NGB representative one)

Nevertheless, it was recognised amongst the participants that this focus on athlete success as a measure of what makes ‘good coaching’ is slowly evolving. There is an awareness of the limits of that measure and that more work should be done around coaching competencies and capabilities. As yet, that framework is not in place or understood. Therefore, there is no objective measure for coaching appointments at high-performance levels because the system is too subjective and in the hands of the ‘few’ that possess power and influence:

[If] you keep producing talented athletes then we’ll say ah ok, come along to a national day, come along to international day, then you are starting to get your name in the frame for international team roles (NGB representative five)

Interviewer: Can you explain the procedures for selecting coaches for international teams? Respondent: No, I wouldn’t be able to answer that one. (NGB representative two)

So, we, from a process point of view, I don’t know the exact process. I think that there is potential improvement there. It could be I think a lot of the time it’s who has been there and done it before. Although last year we did go out to our community and presented them with the opportunity to apply to be involved. There was, I guess an acknowledgement that previously the process has been quite subjective, so we tried to improve the objectivity around opportunities to recruit within team management. Obviously that was open to both males and females and we were trying to offer out the opportunity to gain experience…So from a process point of view, we haven’t established exactly what that looks like and the skill set required, but we are looking to be more transparent in that space and also improve the opportunity for a more objective recruitment of coaches. (NGB representative three)

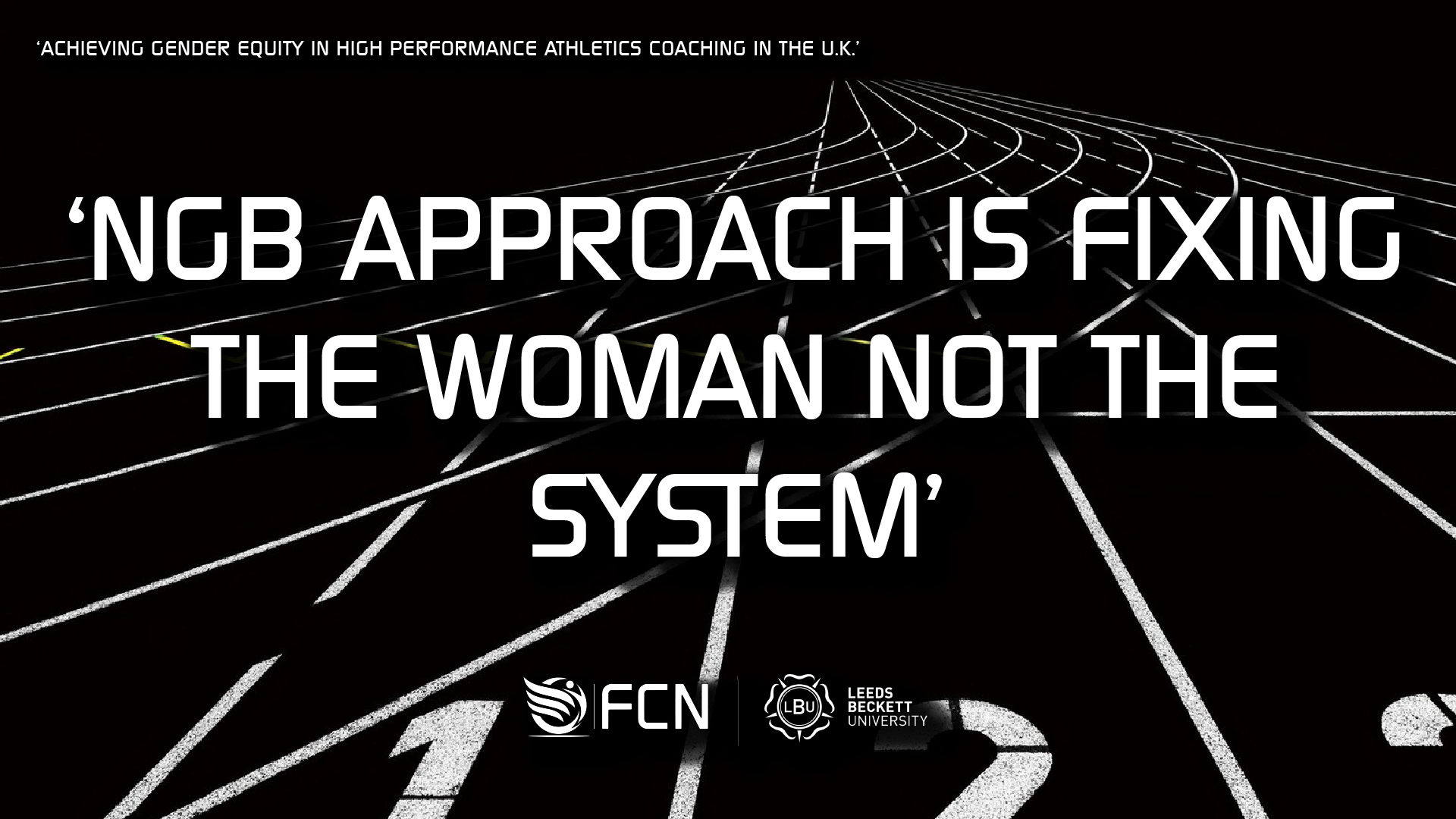

There is clear evidence of a metrics-based culture underpinned by a performance-narrative and one in which quality of coaching is not understood. This cultivates a culture in which gender equity is then understood also in numbers: equity is conceived as a representational issue or an issue of access to the system. It is envisioned that women coaches need merely to be represented, given more opportunities to access the system, or to be equipped or fixed to exist in this system. The danger of this is that the structures that produce such inequities (as described by the coaches in section 2.0) remain untouched and women become then the ‘problem’ that need to be fixed. The consequence too of taking a representational stance to the issue is that organisations risk ‘adding gender and stirring’ to their existing ways of working: women are added into a culture and system that is not conducive for coaches per se. The risk of turnover and negative impact on coach wellbeing is greater because the culture and practices remained unscrutinised. The evidence of this was the participants’ response to what gender equality means to them. For the NGBs, it was a shared assertion that success is seen as men and women have equal access and opportunities to the coaching system:

I think gender equality for me, it doesn’t matter whether it’s in a coaching context, performance or otherwise. For me, gender equality is that women have equal opportunities within any environment…It’s an opportunity to develop and women should be in a position to get the same opportunities as men. (NGB representative four)

[It is] the opportunity for women and men to be able to access that coach pathway. I think that a lot of the barriers are to do with what’s perceived as equal and I think we need to perhaps work more vigorously as an NGB to make, or improve the awareness around the opportunities that we offer for coaches both male and female.(NGB representative three)

Gender equality within a high performance seeing would also mean that both sets of genders were given an equal opportunity or given an equal chance to potentially go for one of the high–performance roles, rather than feeling that they’re only limited (NGB representative one)

It’s about looking at the systemic structures of our organisations, of our qualifications, of our development and have the genders got, not just access to, equal access to. (NGB representative five)

It also means that opportunities for people again regardless of gender, to develop into those roles are supported by the governing body and by the home country athletics federations, by the athletics clubs. (NGB representative two)

The terms ‘equality’ and ‘equity’ were often used interchangeably and conflated. Nevertheless, however the NGB defined it, for these participants, success was also a matter of equalising representation and numbers of women coaches:

Gender equality would be that the end would be that the coaching workforce is representative of…the sport and the makeup of…those participating in the sport… I guess you could divide down at the club coaching level, our coaching workforce should be, is this a phrase…gender equalised against the make-up of the athletes in those clubs. (NGB representative five)

To me, gender equality would simply mean, having an appropriate number of coaches with similar ratios, so having male to female ratios, operating with athletes or operating within an organisation or a club (NGB representative one)

For one NGB, there appeared to be some understanding that gender equity was about focusing on the structures that promoted inclusion or exclusion, that equity would be realised when people are appointed to coaching positions on merit (judged on ability) and when there was a ‘fair’ system in place that rewarded coaches (in terms of pay and promotion). But there was little understanding of culture across all five NGBs and how this culture was supporting an unjust, discriminatory, and exclusive gendered coaching system.